Neurocutaneous Melanosis Presenting with Intracranial Metastasis of Malignant Melanoma

Matilda Bylaite and Thomas Ruzicka

Department of Dermatology, Heinrich-Heine-University Duesseldorf, Duesseldorf, Germany

History

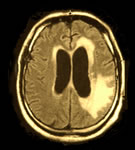

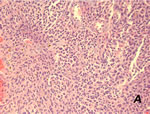

A 37-year-old man with congenital giant and multiple pigmented lesions and a 6-month history of seizures was referred to the Department of Dermatology for further evaluation. His past medical history was unremarkable except for the presence of large and numerous congenital pigmented nevi distributed over his body. He was healthy and had no other complaints until the first neurological symptoms developed. A few months later he was examined by a neurologist after a Grand-mal episode with complaints of headache and slurred speech. Raised intracranial pressure led to mild signs of hydrocephalus. Funduscopy showed papilledema. Cranial computed tomographic (CT) examinations and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain with intravenous contrast revealed meningeal involvement, dilated ventricles and a well-defined oval 2.0 x 1.8 cm contrast-enhanced mesencephalic mass localized at the left parieto-occipital part ( Fig. 1 ). A lumbar puncture was not diagnostic. Temporal craniotomy was performed, and several biopsies were taken from the tumor. Histological analysis of the specimen and immunohistochemistry with S100, MelanA, Vimentin and HMB 45 revealed a metastasis of malignant melanoma ( Fig. 2A and B ). A week later the patient was admitted to our hospital for further evaluation of pigmented lesions and search of the primary malignant melanoma.

| Fig. 1: Axial T1-Gd-enhanced MRI shows meningeal involvement, mesencephalic mass localized at the left parieto-occipital part and dilated ventricles. |

|

|

| Fig. 2A: Intracerebral metastasis of malignant melanoma. Nests of epithelioid tumor cells with large, hyperchromatic nuclei, hematoxylin-eosin staining. |

|

|

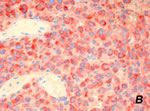

| Fig. 2B: Intracerebral metastasis of malignant melanoma, positive stained malignant cells with immunohistochemical marker HMB 45 |

|

|

Clinical Findings

Physical examination revealed multiple small- to large-sized, raised, hairy, dark-pigmented cutaneous nevi distributed over the face, head, neck, trunk, extremities and even soles and palms. A giant hairy pigmented nevus in an ”old fashioned bathing suit” pattern covered the lumbosacral region, buttocks, pelvis and upper thighs ( Fig. 3A and B ). Excessive scalp skin produced thick, corrugated folds (Pseudocutis verticis gyrata) with large pigmented nevi ( Fig. 4A and B ). There was no evidence of malignancy in any of these cutaneous nevi.

| Fig. 3A: Neurocutaneous melanosis. A giant bathing-trunk congenital melanocytic nevus is associated with multiple satellite nevi |

|

|

| Fig. 3B. Neurocutaneous melanosis. A giant bathing-trunk congenital melanocytic nevus is associated with multiple satellite nevi |

|

|

| Fig. 4A: Pseudocutis verticis gyrata. Excessive, folded skin of the scalp with large pigmented nevi |

|

|

| Fig. 4B: Pseudocutis verticis gyrata. Excessive, folded skin of the scalp with large pigmented nevi |

|

|

Histopathology

Histopathology of skin biopsies from nevi showed nests and linear distribution of nevus cells in dermis and around pilosebaceous and eccrine sweat gland units. There were no signs of atypia or mitosis, and a congenital dermal nevus was diagnosed. Examination and Laboratory Findings

Staging examinations revealed neither lymphogenic nor hematogenic metastasis of malignant melanoma. A psychiatrist diagnosed reactive depression with suicidal thoughts. Laboratory tests did not show any abnormalities. The primary tumor was not found. Diagnosis

In view of the coexistence of the cutaneous and cerebral lesions, a diagnosis of neurocutaneous melanosis with metastasis of malignant melanoma was established. Therapy and Course

The patient received oral glucocorticoids daily. Seizures were managed by using barbiturates. Initially, cranial radiotherapy with Co60 (total 30 Gy) was performed. The patient suffered from nausea, vomiting, lethargy, weakness and loss of appetite. Antiemetics were given. A month later, increased signs of cranial hypertension developed. The patient currently undergoes chemotherapy with temozolomide. Discussion

Neurocutaneous melanosis (NCM) is a rare, congenital, nonheritable phakomatosis in which large or numerous congenital melanocytic nevi are associated with benign and/or malignant melanocytic tumors of the leptomeninges. After the first description by Rokitansky in 1861 (1), over 100 cases of NCM have been reported in the literature. Currently, the NCM criteria of Kadonaga and Frieden are used (2): i) large or multiple congenital melanocytic nevi in association with meningeal melanosis or melanoma; ii) no evidence of cutaneous melanoma, except in patients in whom the examined portions of the meningeal lesions are benign; and iii) no evidence of meningeal melanoma, except in patients in whom the examined areas of cutaneous lesions are benign. So far, the pathogenesis of this disorder remains unclear. NCM is considered to result from defective morphogenesis of embryonic neuroectoderm. Two thirds of patients have giant congenital melanocytic nevi (GCMN) at birth (3). Usually, NCM affects children in early childhood (2). CNS involvement commonly manifests as increased intracranial pressure, seizures, psychiatric disturbance and infrequently, cranial nerve palsies. The disease may be associated with other neurocutaneous syndromes such as Sturge-Weber or neurofibromatosis, also developmental anomalies such as Dandy-Walker complex, spinal lipoma or arachnoid cyst (2-4). MRI of the brain and histological findings are essential to confirm the diagnosis. Once the neurological symptoms manifest, the course is usually progressive and fatal. Neither radiotherapy nor chemotherapy seem to improve the outcome (5). However, giant congenital lesions have a definite lifetime risk of melanoma, with estimates ranging from 5-15% (3, 7). The exact risk of NCM for patients with GCMN remains unknown. Unfortunately, central nervous system melanomas are present in 40-60% of these patients (5, 6). Our adult case of NCM with late onset of symptoms and intracranial metastasis of malignant melanoma is very rare. It illustrates the importance of lifetime follow-up by dermatologists and neurologists of patients with large or multiple congenital melanocytic nevi. Early diagnosis may improve the survival time. References

1. Rokitansky, J. Ein ausgezeichneter Fall von Pigment-Mal mit ausgebreiteter Pigmentierung der inneren Hirn- und Rückenmarkshäute. Allgem Wien Med Z 1861, 6: 113-6.

2. Kadonaga, J.N., Frieden, J. Neurocutaneous melanosis. Definition and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991, 24: 747-55.

3. Kadonaga, J.N., Barkovich, A.J., Edwards, M.S., Frieden, I.J. Neurocutaneous melanosis in association with the Dandy-Walker complex. Pediatr Dermatol 1992, 9: 37-43

4. DeDavid, M., Orlow, S.J., Provost, N. et al. Neurocutaneous melanosis: clinical features of large congenital melanocytic nevi in patients with manifest central nervous system melanosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996, 35: 529-38.

5. Chu, W.C.W., Lee, V., Chan, Y.L. et al. Neurocutaneous melanomatosis with rapidly deteriorating course. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2003, 24: 287-90.

6. Bittencourt, F.V., Marghoob, A.A., Kopf, A.W., Koenig, K.L., Bart, R.S. Large congenital melanocytic nevi and risk for development of malignant melanoma and neurocutaneous melanocytosis. Pediatrics 2000, 106: 736-41

7. Di Rocco, F., Sabatino, G., Koutzoglou, M., Battaglia, D., Caldarelli, M., Tamburrini, G. Neurocutaneous melanosis. Childs Nerv Syst 2004, 20: 23-8. |